Table of Contents

- Video of Building Social Presence in CALL

- Challenges in Implementing CALL Effectively

- The Role of Communication Technologies in CALL

- Social Dimensions of CALL and Collaborative Learning

- Limitations in Pedagogical Integration of Technology

- The Importance of Social Presence in Online Learning

- Toward an Integrative and Socially Interactive CALL

- Fostering Social Presence in CALL

- Strategies for Enhancing Online Interaction

- References

Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) has gained recognition as a key component of English education in the digital age, yet its implementation still faces important challenges. Success in online learning requires more than just advanced technology; it depends on fostering social presence, collaboration, and interaction among learners and teachers. This article examines how peer-assessment, negotiation of meaning, and content-based instruction can strengthen CALL and improve learner satisfaction.

Video of Building Social Presence in CALL

Challenges in Implementing CALL Effectively

Despite the recognition of the importance of CALL in teaching and learning English as the international language in the third millennium, it appears that its practical implementation has not received adequate attention. In other words, online L2 learners could achieve a higher level of success and satisfaction in comparison to their current one, providing that some essential modifications were made to CALL, which will be discussed in this article.

The scarcity of established norms for CALL research might be regarded as a weakness of the field, placing some restrictions upon its efficacy to come up with established findings (Hubbard, 2009). It might indicate that more systematic research should be conducted to investigate the shortcomings of CALL implementation pathologically. To be more precise, furnishing all the technological requirements and facilities cannot necessarily guarantee success in teaching and learning English online.

The Role of Communication Technologies in CALL

In this regard, Herring (2007) calls for a more critical analysis of communication technology in computer-mediated communication (CMC) because she believes that “computer networks do not necessarily guarantee democratic, equal-opportunity interaction” (Herring, 2007, p. 13). However, some scholars like Broad, Matthews and McDonald (2004) believe that enhancing the new technologies of the Web is of primary importance because it can maximize the access of appropriate resources within a particular subject environment.

Social Dimensions of CALL and Collaborative Learning

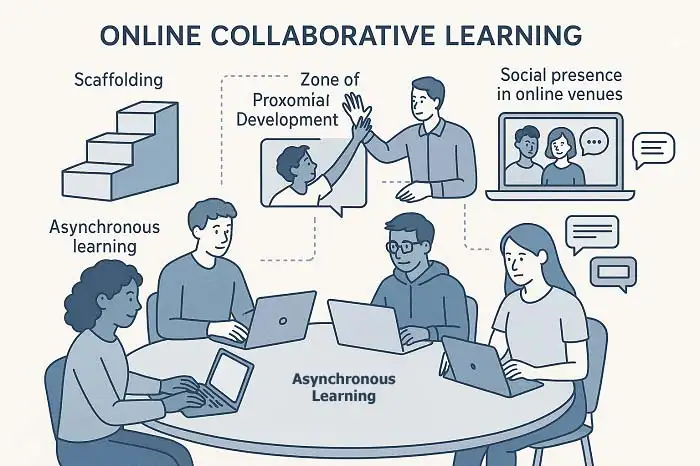

A significantly theoretical factor with respect to CALL has something to do with its social dimension, something which deserves even more consideration because as Kenning (2007) has wisely proposed, “learning is increasingly conceived in educational circles as the result of collaborative actions that often involve gaining support from peers as well as teachers” (p. 113).

For instance, AbuSeileek (2007) contends that cooperative computer learning is regarded as a functional and result-oriented technique for the following two reasons:

- The production of a group is normally greater than that of an individual.

- Each member of the group can positively take advantage of their peers in the group.

However, from a sociocultural point of view in conjunction with second language acquisition (SLA), Interactional Accounts (IAs), according to Harrington and Levy (2001), are de-emphasized in CALL programs because the IAs focus on the face-to-face interaction of the learners and an interlocutor in terms of the individual participants, independent of context.

In this regard, in conjunction with the significance of social considerations in CMC, Walther (1996) declares that “combinations of media attributes, social phenomena, and social-psychological processes may lead CMC to become hyperpersonal, that is, to exceed FtF interpersonal communication” (p. 5), a phenomenon which was also referred to as social information processing (SIP) (Walther, 1997).

Limitations in Pedagogical Integration of Technology

According to Kessler and Plakans (2008), if discretion is not practiced, teachers’ technological skills may mask their ability to effectively integrate their technological expertise in a pedagogically sound manner. The limitation of all these interpretations is that, as Ridder (2000) has stated, although many things have been said about what to teach and learn in online classes, little is known about how to teach and learn the content in virtual venues.

Although there has been a battery of empirical analysis in support of the positive nature of interactive learning in education, there is still little evidence to suggest that the use of the Web can improve the learning environment, and as a result, the experience of students (Broad et al., 2004). The aspect of creating an effective online community, in which the L2 learners can maximize their interaction and involvement in online courses and activities, has not been given adequate attention.

For instance, Jiang and Ramsay (2005) argue that building up rapport among online L2 learners is crucial for interaction because it can:

- make the process of learning more enjoyable for the learners,

- increase the level of motivation in the learners, and

- reduce the level of anxiety in them.

In this regard, it should be pointed out that the feasibility of creating a successful online learning community has become assured, thanks to the availability of myriads of state-of-the-art technologies, software programs and electronic equipment.

The Importance of Social Presence in Online Learning

The majority of CALL-based education systems nowadays are not categorized as being integrative (Felix, 2001). In such education systems, CALL practitioners generally attempt to compartmentalize the whole system into individual variables, namely reading ability, acquisition of grammar, elicitation tasks, motivation and attitude, discourse analysis, etc., whereas “no large-scale multivariable investigation focusing on the students’ experience of Web-based language learning has been reported to date” (Felix, 2001, p. 47).

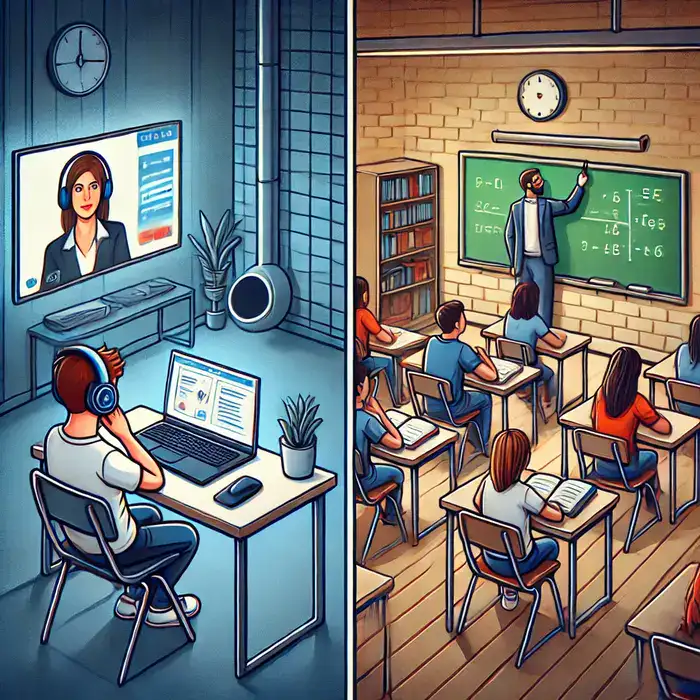

In these educational programs, L2 learners can seldom develop a sense of belonging to the online community, their peers and the teacher due to the fact that the concept of social presence has not been truly realized. Social presence in online communities signifies that the members have a belonging to each other and matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that the member’s needs will be satisfied through their commitment to be together (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). The saliency of establishing social presence in an integrative CALL-based educational program lies at heart of the unique nature of online learning in virtual environments, according to which learners do not have face-to-face interaction with each other.

As a consequence, the e-teacher is supposed to fill in this gap (i.e., compensating for no actual face-to-face interaction) in one way or another. According to James (1996), with the intention of creating an interactive learning community, the teacher ought to evaluate the material and content of the course critically to come up with interactive exercises and activities rather than simply assume that groups of L2 learners working on a common task would actualize optimum interaction automatically. For instance, the teacher might motivate the students through the implementation of CBI in which the students could practice self- and peer-assessment and have negotiation of meaning in a truly interactive fashion.

Toward an Integrative and Socially Interactive CALL

As discussed earlier, the most recent genre of CALL has an integrative and socially interactive essence, which requires the researcher to study the phenomenon in more depth. Some scholars in the field of using technology for academic purposes (e.g., Cobb, 2009; Hubbard, 2009; Leahy, 2008; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Tu, 2001; Warschauer, Grant, Real & Rousseau, 2004) have conducted qualitative studies to come up with more profound and mature analyses. They all maintain that qualitative analyses of interactions might provide more comprehensive answers.

To be more specific, Tu (2001) declares that the sociology of everyday life regards the actions of people as the results of a process during which meanings that are constructed in everyday social interactions are used as the basis for individual actions. In this regard, this study seeks to break the allegedly unquestionable rule of overemphasizing quantitative methods for conducting research in social sciences, which could be regarded as one of the obstacles to arriving at more in-depth findings.

In sum, although the training of CALL has developed over the last thirty years, the training of student interaction and involvement in virtual venues has still remained a low priority, confirming Warschauer, Turbee and Roberts’ (1996) view that involving the students in determining the class direction does not necessarily imply that teachers assume passive roles. Teachers’ contribution in a learner-centered, network-enhanced classroom includes coordinating group planning, focusing students’ attention on linguistic aspects of computer-mediated texts, helping students to gain metalinguistic awareness of genres and discourses, and assisting students in developing appropriate learning strategies.

Fostering Social Presence in CALL

The central aim of this research is to examine how social presence can be generated in CALL programs, a relatively underexplored but essential area of online learning. This study seeks to engineer an online social context by modifying student-student and teacher-student interaction patterns. A key focus is on the impact of peer-assessment, online negotiation of meaning, and student-based content development during a year-long English conversation class.

Strategies for Enhancing Online Interaction

This research also investigates the role of content-based instruction (CBI), particularly through carefully selected and engaging themes that stimulate negotiation of meaning both synchronously and asynchronously. Special attention is given to asynchronous peer-assessment, such as replying to classmates in comment forms, forums, and chat rooms, as well as synchronous interaction in live classes. The goal is to critically evaluate and refine interaction patterns—peer-assessment, negotiation of meaning, student-driven CBI, and teacher-student engagement—that can enhance social presence in CALL environments.

References

- AbuSeileek, A. F. (2007). Cooperative vs. individual learning of oral skills in a CALL environment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 20(5), 493-514. doi:10.1080/09588220701746054

- Broad, M., Matthews, M., & McDonald, A. (2004). Accounting education through an online-supported virtual learning environment. Active Learning in Higher Education, 5(2), 135-151. doi:10.1177/1469787404043810

- Cobb, S. C. (2009). Social presence and online learning: A current view from a research perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8(3), 241-254.

- Felix, U. (2001). The web’s potential for language learning: The student’s perspective. ReCALL, 13(1), 47-58. doi:10.1017/s0958344001000519

- Harrington, M., & Levy, M. (2001). CALL begins with a “C”: Interaction in computer-mediated language learning. System, 29, 15-26. doi:10.1016/s0346-251x(00)00043-9

- Herring, S. C. (2007). Computer-mediated discourse. In D. Tannen, D. Schiffrin & H. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 612-634). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9780470753460.ch32

- Hubbard, P. (2009). Educating the CALL specialist. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 3(1), 3-15. doi:10.1080/17501220802655383

- James, R. (1996). CALL and the speaking skill. System, 24(1), 15-21. doi:10.1016/0346-251x(95)00050-t

- Jiang, W., & Ramsay, G. (2005). Rapport-building through CALL in teaching Chinese as a foreign language: An exploratory study. Language Learning and Technology, 9(2), 47-63.

- Kenning, M. M. (2007). ICT and language learning: From print to the mobile phone. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kessler, G., & Plakans, L. (2008). Does teachers’ confidence with CALL equal innovative and integrated use? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 21(3), 269-282. doi:10.1080/09588220802090303

- Leahy, C. (2008). Learner activities in a collaborative CALL task. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 21(3), 253-268. doi:10.1080/09588220802090295

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23. doi:10.1002/1520.6629(198601)14:1%3C6::aid-jcop2290140103%3E3.0.co;2-i

- Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. JALN, 7(1), 68-88.

- Ridder, I. D. (2000). Are we conditioned to follow links? Highlights in CALL materials and their impact on the reading process. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 13(2), 183-195. doi:10.1076/0958-8221(200004)13:2;1-D;FT183

- Tu, C. H. (2001). How Chinese perceive social presence: An examination of interaction in online learning environment. Educational Media International, 38(1), 45-60.

- Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23, 3-43. doi:10.1177/009365096023001001

- Walther, J. B. (1997). Group and interpersonal effects in international computer-mediated communication. Human Communication Research, 23(3), 342-369. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00400.x

- Warschauer, M., Grant, D., Real, G. D., & Rousseau, M. (2004). Promoting academic literacy with technology: Successful laptop programs in K-12 schools. System, 32(1), 525-537. doi:10.1016/j.system.2004.09.010

- Warschauer, M., Turbee, L., & Roberts, B. (1996). Computer learning networks and student empowerment. System, 24(1), 1-14. doi:10.1016/0346-251x(95)00049-p 230 INTERACTIVITY AND SOCIAL PRESENCE IN CALL