Table of Contents

- Video on Questions & Hypotheses on Social Presence

- Research Questions

- Research Hypotheses

- The Role of Social Context in CALL

- Teacher Interaction: Intimacy vs. Immediacy

- Building a Sense of Community in Virtual Venues

- Assessment Methods and Their Role in CALL

- Content-Based Instruction (CBI) and Learner Involvement

- Negotiation of Meaning in Online English Classes

- References

This study explores how Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) can foster stronger social presence, collaboration, and engagement in online English classes. By examining teacher–student interaction, assessment methods, negotiation of meaning, and Content-Based Instruction (CBI), the research identifies strategies for building interactive and supportive learning communities. The proposed research questions and hypotheses aim to highlight the most effective approaches for integrating technology with pedagogy, helping online English teachers create more dynamic, socially connected, and student-centered virtual classrooms.

Video on Questions & Hypotheses on Social Presence

Research Questions

The current study is aimed at seeking appropriate and comprehensive answers to the following research questions. It is proposed that by implementing the strategies and techniques investigated throughout this study, the settings of CALL-based educational programs could become more integrative, interactive, and socially oriented, which per se makes it feasible for the students to maximize L2 learning in virtual venues.

- What are the most important characteristics of a successful social context in an integrative CALL?

- How should an online English teacher interact with L2 learners to promote more collaboration among them?

- How can an online English teacher create a sense of belonging and community in L2 learners?

- Which type of assessment (self-assessment, peer-assessment, or teacher-assessment) is more crucial in creating social presence in conjunction with CALL?

- How could Content-Based Instruction (CBI) help online L2 learners and teachers to become more actively involved?

- What is the impact of negotiation of meaning in online English conversation classes on establishing an operationally interactive learning community?

Research Hypotheses

The Role of Social Context in CALL

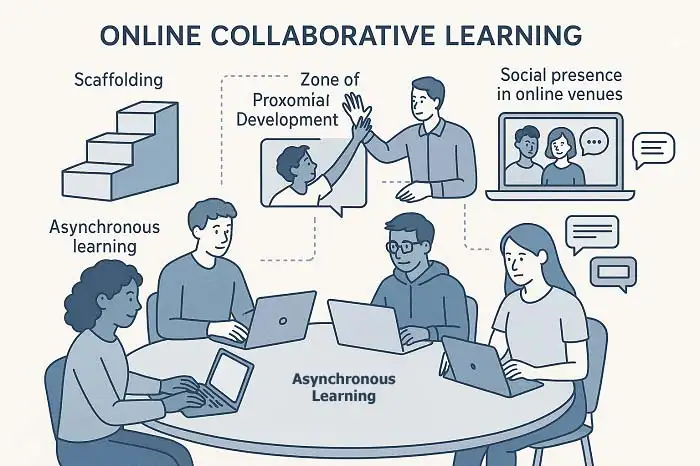

The social context of CALL programs is regarded as one of the substantial ingredients of social presence (Tu, 2001) in which some level of uncertainty about complex tasks might trigger social communication among computer-mediated communication users (Steinfield, 1986) to be able to form stereotypical impressions of their partners on the basis of language, typographic, and contextual cues (Walther, 1997).

It is presumed that as long as the concept of social context is concerned, between the two modes of computer-mediated communication (i.e., synchronous and asynchronous), the latter might be more effective to generate the sense of social presence. As Smith and Gorsuch (2004) have argued, some potentially important information may be lost during the message construction phase. On the other hand, Brooke (2012) maintains that asynchronous CMC can help the students to manage their affective barriers (feelings of anxiety and stress) in their interaction as they have enough time to reflect upon and formulate their thoughts before expressing them in CMC. This research is going to investigate whether this hypothesis is tenable or not.

Teacher Interaction: Intimacy vs. Immediacy

With respect to the e-teacher’s interaction with online students, some scholars including Picciano (2002) and Baker (2010) assert that the teacher should constantly be present. That is to say, his/her virtual visibility must always be perceived by the learners.

In relation to the quality of the teacher’s interaction with the students in CMC, there has always existed the famous dichotomy of intimacy or immediacy (Cobb, 2009). Argyle and Dean (1965) conceptualized intimacy as one of the building blocks of successful interaction, which is inspired by some factors, namely physical distance, eye-contact, personal topics of conversation, smiling, and affiliation. Wiener and Mehrabian (1968, as cited in Cobb, 2009) regarded immediacy as a measure of psychological distance that an interactor considers between themselves and the object of their interaction.

The conductor of this study assumes that concerning the interaction of the teacher with the students, between the two major factors of intimacy and immediacy, the latter appears to be more influential in CALL programs, and in this research, it will be attempted to cast more light on this dichotomy.

Building a Sense of Community in Virtual Venues

With the intention of creating a sense of community among L2 learners in virtual venues, especially in conversation classes, according to Ko and Rossen (2010), the teacher is expected to help the learners to break the ice and motivate them to participate in the discussions. This could be realized by assigning less challenging topics at the start so that all the participants could have enough self-confidence to express and exchange their information.

McMillan and Chavis (1986) consider the following four factors to be the ingredients of establishing a sense of community in online classes:

- Comprising or a sense of belonging

- The ability to influence the group

- Realization of needs through goals that are shared among the learners

- Rapport among the learners in the group

Among the four elements to establish a sense of community proposed by McMillan and Chavis (1986), the researcher believes that the third and fourth factors (i.e., needs fulfillment and shared connections) are more effectual in building a sense of community among L2 learners. This is because, in the long term, if the students’ academic needs are not met, they might end up losing their interest in continuing the course, albeit a truly interactive one.

Assessment Methods and Their Role in CALL

With respect to the role of assessment, Gaytan and McEwen (2007) assert that, “effective assessment techniques include projects, portfolios, self-assessments, peer evaluations, weekly assignments with immediate feedback, timed tests and quizzes, and asynchronous type of communication using the discussion board” (p. 129).

In this regard, it is hypothesized that among self-assessment, peer-assessment and teacher-assessment, the second one (i.e., peer-assessment) could be comparatively more persuasive to account for an integrative and interactive genre of CALL. This remains a hypothesis that is going to be put to the test.

Content-Based Instruction (CBI) and Learner Involvement

With reference to the research question on the impact of CBI on student involvement in online courses, Tella (1992) conducted a study in which two CALL-based groups of participants were encouraged to exchange ideas on the basis of CBI via email. In the first group, the students could opt for topics, and in the second one, the topics or themes were imposed upon them by the teacher.

The results showed that the students who could select the topics and write about them via email increased their engagement and autonomy in the online course in comparison to the other group. The participants of this investigation were expected to write questions on the assigned topics for discussion in the form of comments before each session, which was called Round Table. It is presumed that raising questions on the part of the students (and not the teacher) could be more effective than teacher-driven CBI in augmenting the level of social presence in online courses.

Negotiation of Meaning in Online English Classes

Regarding the last research question about the effect of negotiation of meaning on student interaction in integrative CALL programs, Arcos and Sánchez (2006) contend that negotiation of meaning does exist even in classes based on audio-conferences despite the absence of nonverbal communication. They add that the teacher in virtual venues should not be in the limelight. Instead, he/she is expected to engage the students’ attention and interest to practice negotiation of meaning on their own.

In this regard, this study is going to put this theory to the test: with the intention of encouraging negotiation of meaning in CALL programs, the teacher ought not to be in the foreground of attention. That is to say, the teacher should adopt a neutral position to the topic being discussed. Meanwhile, it is on the part of the teacher to provide the students with an unbiased atmosphere in which they could freely express and exchange their ideas nonjudgmentally.

References

- Arcos, B. D. I., & Sánchez, I. A. (2006). Ears before eyes: Expanding tutors’ interaction skills beyond physical presence in audio-graphic collaborative virtual learning environments. In P. Zaphiris & G. Zacharia (Eds.), User-centered computer aided language learning (pp. 74-93). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Inc. doi:10.4018/978-1-59140-750-8.ch004

- Argyle, M., & Dean, J. (1965). Eye-contact, distance and affiliation. Sociometry, 28(3), 289-304. doi:10.2307/2786027

- Baker, C. (2010). The impact of instructor immediacy and presence for online student affective learning, cognition, and motivation. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(1), 1-30. 209 INTERACTIVITY AND SOCIAL PRESENCE IN CALL

- Brooke, M. (2012). Why asynchronous computer-mediated communication (ACMC) is a powerful tool for language learning? Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 2(3), 125-129. doi:10.4236/ojml.2012.23016

- Cobb, S. C. (2009). Social presence and online learning: A current view from a research perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8(3), 241-254.

- Gaytan, J., & McEwen, B. C. (2007). Effective online instructional and assessment strategies. The American Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 117–132.

- Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2010). Teaching online: A practical guide (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23. doi:10.1002/1520.6629(198601)14:1%3C6::aid-jcop2290140103%3E3.0.co;2-i

- Picciano, A. G. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. JALN, 6(1), 21-40.

- Smith, B., & Gorsuch, G. J. (2004). Synchronous computer mediated communication captured by usability lab technologies: New interpretations. System, 32, 553-575. doi:10.1016/j.system.2004.09.012

- Steinfield, C. W. (1986). Computer-mediated communication in an organizational setting: Explaining task-related and socioemotional uses. In M. L. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication yearbook 9 (pp. 777-804). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tella, S. (1992). Talking shop via e-mail: A thematic and linguistic analysis of electronic mail communication. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki University Press.

- Tu, C. H. (2001). How Chinese perceive social presence: An examination of interaction in online learning environment. Educational Media International, 38(1), 45-60.

- Walther, J. B. (1997). Group and interpersonal effects in international computer-mediated communication. Human Communication Research, 23(3), 342-369. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00400.x