Table of Contents

- Video of language curriculum development

- Abstract

- History of curriculum development

- History of language curriculum development

- Vocabulary selection

- Grammatical syllabuses

- Structural syllabuses:

- Situational syllabuses

- Notional/Functional Syllabuses

- ESP

- EAP

- Content-based Instruction

- Context + Content

- Task-based Syllabuses

- Needs analysis

- Humanistic Education in Curriculum

- Reconceptualization

- Conclusion

- References

- How to cite this article in APA Style?

The history or origin of language curriculum development in second language acquisition (SLA)

Author: Dr. Mohammad Hossein Hariri Asl

Video of language curriculum development

Abstract

Curriculum development, in the course of time, has undergone some changes to improve itself. Meanwhile, language curriculum development seems to be closer to modification and improvement over time. The history of language curriculum development reflects a trend from systematic and structural towards more functional and contextualized. In this study, it was attempted to glean as much relevant information as possible on the above-mentioned trend chronologically. It was clarified that the implementation of needs analysis, in a humanistic and negotiated manner, led to some reconceptualization in the field of language curriculum. To be more precise, apart from linguistic considerations, some other aspects, such as sociocultural, functional-notional and communicative dimensions of language teaching were also taken into consideration. As a result, Task-based, Content-based, and Project-based syllabi came into being, in which learners’ needs and interests were also taken into account. In the end, it is important to add that history never ends, that is, the process of language curriculum is an ongoing one, which constantly updates itself. Consequently, we should expect some further modifications to it in the future.

History of curriculum development

There are two foundational works on curriculum, one by Ralph Tyler (1949) and the other by Jerome Bruner (1960). These provide a good beginning, not only because they were among the first books on curriculum to be published but because the ideas they contain have been among the most enduring. Indeed, they continue to provide the foundation for most current thinking in curriculum development (Howard, 2007).

In 1959, at Woods Hole on Cape Cod, a group of 35 scientists, scholars and educators met with the purpose of discussing how to improve science education, to “examine the fundamental processes involved in imparting to students a sense of the substance and method of science” (Bruner, 1960, p. xvii, as cited in Howard, 2007). The meeting was sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences and over the course of the ten day meeting, several important themes emerged that were to have major implications not only for science education, but for education in general.

The Comenian curriculum is founded on the concept of natural order as the true reflection of divine order, a seventeenth-century concept which finds an echo in all contemporary science from Kepler to Newton (Howatt, 1984).

History of language curriculum development

It is called The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) and was intended, as the title suggests, to be the first section of a large-scale work on the basic school curriculum which would transform education in England by replacing the traditional medieval structure of the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic) and of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) with a new system founded oil vernacular literacy.

Claudius Holyband, in the 16th century, was the leading professional language teacher of his day and therefore the man whose work and teaching methods we know most about. His principal work was teaching French to young children at a succession of schools he founded in and near London. Holyband’s career gives us a clear picture of the high level of pedagogical expertise that the immigrant group at its best brought to their language teaching activities (Howatt, 1984).

During his time in London, Holyband opened three schools at different times in which he taught French to young children as well as offering the standard Latin curriculum which parents would want and expect.

Apart from brave attempts by men like Holyband and his fellow- refugees to run schools in which classical and vernacular languages were taught side-by-side, the teaching of modern languages remained a small-scale enterprise, usually with a private tutor but occasionally in small classes, throughout the seventeenth century (Howatt, 1984). The main concern of the schools was the teaching of Latin and to some extent Greek, and until the private schools and academies put down strong roots in the early eighteenth century, the classical curriculum was dominant and unchallenged.

A more puritanical philosophy of education was set out at some length in Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning (1605, as cited in Howatt, 1984) which reached its most elaborate expression in the work of Jan Amos Comenius.

Jan Amos Comenius (1592—1670, as cited in Howatt, 1984) was a genius, possibly the only one that the history of language teaching can claim, and like many geniuses, his practical achievements fell a long way short of his aspirations* He produced two major works of lasting educational significance in his late thirties, the Janua Linguarum Reserata, an intermediate-level textbook for the teaching of Latin, which was completed in 1631, and the Czech version of his Great Didactic, though the latter was not published in its final Latin form until 1657.

It is rather ironical that Comenius should be remembered for writing Latin textbooks when what he really wanted was a system of education in which the mother tongue would play the central role and foreign languages would be learnt as and when they were needed for practical purposes. He believed that foreign vernacular languages should be taught as a means of communication with the people of neighboring countries, and that the classical languages, which were still required for certain academic and professional purposes, should not claim more than their fair share of curriculum time.

In the introduction to the Janua hinguarumy he says explicitly that Latin studies should be completed in a year-and-a-half ‘at the farthest’, and there was no need for excessive zeal and thoroughness: ‘the complete and detailed knowledge of a language, no matter which it be, is quite unnecessary and it is absurd and useless on the part of anyone to try and attain it.

To Comenius, content and not form was of overriding importance. In this he agreed with Milton who said in his essay Of Education in 1644: “though a Linguist should pride himself to have all the Tongues that Babel cleft the world into, yet, if he have not studied the solid things in them as well as the Words and Lexicons, he were nothing so much to be esteemed a learned man, as any Yeoman or Tradesman competently wise in his Mother Dialect only”.

It was towards this “great and common world’ that Comenius, following Bacon, wanted to lead his pupils in their exploration of nature through the senses. Language, or ‘the right naming of Things’, was the means whereby these perceptions would be transformed into knowledge and an understanding of the unity of God and nature in universal love and wisdom.

The absence of French from the public school curriculum (though it was marginally more successful in the private sector) is all the more remarkable considering the prestige which the language enjoyed after the Restoration both as a social accomplishment and, more seriously, as an essential element in the training of court officials, diplomats, and the like.

There are three major strands in the development of language teaching in the nineteenth century which twine together in the great controversies of the last two decades. The first is the most obvious and the best chronicled, namely the gradual integration of foreign language teaching into a modernized secondary school curriculum. In 1800 very few schools taught foreign languages except as optional ‘extras’ to the principal work of the school, the teaching of classical languages. By 1900 most secondary schools of what could genetically be called ‘the grammar school type* had incorporated one or more of the major European languages into their core curriculum.

In England the most significant development in middle-class education, and the device that levered modern languages on to the secondary school curriculum, was the establishment in the 1850s of a system of public examinations controlled by the universities. The 4washback effect’ of these examinations had the inevitable result of determining both the content of the language teaching syllabus and the methodological principles of the teachers responsible for preparing children to take them.

The Locals, as the examinations were known, increased the status of both modern languages and English by including them on the curriculum alongside the classical languages. Basedow (1723-1790, as cited in Howatt, 1984) founded a school called the Philanthropinum at Dessau which followed a ‘natural’ curriculum that included crafts, outdoor activities, and a conversational approach to language teaching.

The field of language teaching has undergone profound changes during the last 30 to 40 years. The expanded scope of language teaching programs around the world has led to a need for new technology in language teaching (Brown, 1995). Increasingly, successful language programs depend upon the use of approaches drawn from other domains of educational planning. This often involves the adoption of what has come to be known as the systematic development of language curriculum, that is, a curriculum development approach that views language teaching and language program development as a dynamic system of interrelated elements.

Brown (1995) believes, “Language teachers have long been faced with a plethora of methods from which to choose” (p. 1). Anthony (1965, as cited in Brown, 1995) argues that this bewildering variety of labels has evolved because, “over the years, teachers of language have adopted, adapted, invented and developed a bewildering variety of terms which describe the activities in which they engage and the beliefs that they hold” (p. 93).

In an attempt to find patterns in the confusion of language teaching methodology, McKay (1978, as cited in Brown, 1995) describes the types of syllabuses that have been used in language teaching. She points to three ways of organization that have appeared during the history of language teaching: Structural syllabuses, situational syllabuses, and notional syllabuses.

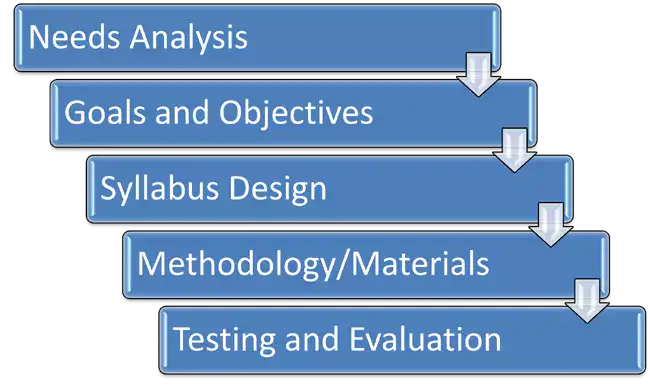

The history of curriculum development in language teaching starts with the notion of ‘syllabus design’. As Richards (2001) has said, “syllabus design is one aspect of curriculum development but is not identical with it” (p. 2). Curriculum development in language teaching began in the 1960s, though issues of syllabus design emerged as a major factor in language teaching much earlier.

Much of the impetus for changes in approaches to language teaching came about from changes in teaching methods. According to Richards (2001), “although methods are specifications for the processes of instruction in language teaching, that is, questions of how, they also make assumptions about what needs to be taught, that is, the content of instruction” (p. 3).

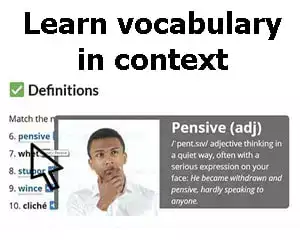

In any language program, a limited amount of time is available for teaching. One of the first problems to be solved is deciding what would be selected from the total corpus of the language and incorporated in textbooks and teaching materials. This came to be known as the problem of ‘selection’ (Richards, 2001). Two aspects of selection received primary attention in the first few decades of the twentieth century: vocabulary selection and grammar selection.

Vocabulary selection

A lexical approach to language teaching refers to one derived from the belief that the building blocks of language learning and communication are not grammar, functions, notions, or some other unit of planning and teaching but lexis, that is, words and word combination. Several approaches to language learning have bbeen proposed that view vocabulary and lexical units as central in learning and teaching. These include The Lexical Syllabus (Willis, 1990), Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching (Nattinger & DeCarrico, 1992), and the Lexical Approach (Lewis, 1993, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001).

In 1983, Dave Willis and his wife, Jane Willis, were commissioned by Collins to write a new English course to be called the Collins COBUILD English Course (Willis, 1990). The rationale and design for lexically based language teaching described in The Lexical Syllabus (Willis, 1990, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001) and its application in the Collins COBUILD English course represent the most ambitious attempt to realize a syllabus and accompanying materials based on lexical rather than grammatical principles.

Willis (1990, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001) notes that the COBUILD computer analyses of texts indicate that “the 700 most frequent words of English account for around 70% of all English text”. This fact led to the decision that “word frequency would determine the contents of our course” (p. vi).

According to Richards (2001), some of the earliest approaches to vocabulary selection involved counting large collections of texts to determine the frequency with which words occurred, since it would seem obvious that words of highest frequency should be taught first. The earliest frequency counts undertaken for language teaching were based on analysis of popular reading materials and resulted in a word frequency list. This was in the days before tape recorders made possible the analysis of words used in the spoken language and before computers could be used to analyze the words used in printed sources.

The procedures of vocabulary selection led to the compilation of a ‘basic vocabulary (or what is now called a lexical syllabus), that is, a target vocabulary for a language course usually grouped or graded into levels. According to White (1988), Palmer’s interest in controlled vocabulary coincided with that of Michael West, whose name is closely associated with two important developments: the New Method Readers, and General Service List of English Words.

The heart of the Scientific Study is the organization of the curriculum or syllabus, ‘the Ideal Standard Programme’ as Palmer called it.

The New Method Readers by Michael West (1888-1973) are the first Language teaching materials to have emerged from an experimental project (Howatt, 1984). The project itself was written up in a report called Bilingualism (with special reference to Bengal) published by the Indian Bureau of Education in 1926 and also provided the data for West’s D. Phil, awarded by the University of Oxford in 1927 under the title: ‘The Position of English in a National System of Education for Bengal’.

West, in Bengal, carried out what we would now call a ‘needs analysis’ and the results of his survey were published in a report in 1926, in which he advocated developing practical information reading in English, which would enable Bengalis to have access to the technological knowledge needed for economic development of their country. He proposed two main ways of improving reading texts for children; first, simplifying the vocabulary by replacing old-fashioned literary words with more common modern equivalents; and second, by applying the principles of readability and lexical distinction by presenting fewer words more often.

Willis (1990) explains the future trends in lexical syllabus in this way:

In one way this took us back to the pioneering work in the analysis of lexis of scholars like West and Thorndike in the 30s and 40s. But the computer would be able to afford a much more thorough and efficient analysis than had been possible in those days. The database assembled at Birmingham would provide us with detailed information about the commonest words and patterns in English and the meanings and use of those words and patterns. At first we had doubts about the practicality of the lexical syllabus. But the more we worked with the information supplied by the COBUILD research team the more we became convinced that the syllabus which emerged was highly practical, entirely realistic and vastly more efficient than anything we had worked with before (p. vi).

In this response, White (1989) maintains:

And it is only West who began his career with what we now refer to as Third World experience and, indeed, he may be credited with conducting the first major needs analysis in relation to the broader developmental requirements of West Bengal (p. 1).

In one respect, Willis’s (1990) COBUILD computer analysis resembled the earlier frequency-based analyses of vocabulary by West (1953) and Thorndike and Longue (1944, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001). The difference in the COBUILD course was the attention to word patterns derived from the computer analysis. Willis (1990, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001) stresses that “the lexical syllabus not only subsumes a structural syllabus, it also indicates how the structures which make up syllabus should be exemplified” (p. vi).

The importance of lexical competence is so great that even Chomsky who used to place a lot of emphasis on syntax has recently adopted a ‘lexicon-is-prime’ position in his Minimalist Linguistic Theory (Cook & Newson, 2007).

Later on, Pienemann’s (1998) Processability Theory and Bresnan’s (1982) Lexical-Functional Grammar was designed to overcome the limitations of the strategies approach by which it was originally inspired (Pienemann, 1998).

Grammatical syllabuses

Although language teaching has a long history stretching back to ancient times, the ways of describing language remained little changed until this century (Howatt, 1984, as cited in Hutchinson & Waters, 1987).

The need for a systematic approach to selecting grammar for teaching purposes was a priority for applied linguists from the 1920s. From this time, a number of attempts have been made to develop basic structure lists for language teaching (e.g., Fries, 1952; Hornby, 1954; Alexander, Allen, Close & O’Neill, 1975, as cited in Richards, 2001). According to Richards (2001):

In regard to the teaching of English, form the 1930s, applied linguists began applying principles of selection to the design of grammatical syllabuses. But in the case of grammar, selection is closely linked to the issue of gradation. Gradation is concerned with the grouping and sequencing of teaching items in a syllabus. A grammatical syllabus specifies both the set of grammatical structures to be taught and the order in which they should be taught (p. 10).

Structural syllabuses:

In the 1960s, it was taken for granted that a structural syllabus, based on widely accepted principles of selection and grading as outlined by Palmer and Hornby would form the premise of language teaching materials and in retain, two such courses published during this decade became international best sellers: L. G. Alexander’s New Concept English (1967) and G. Broughton’s Success with English (1968, as cited in White, 1988).

These courses also employed teaching procedures which combined features of the situational method and audio-visual techniques, while many of the controlled and guided practice activities shoed similarities to those found in American Audiolingualism.

This syllabus consists of an inventory of grammatical, phonological and lexical items, graded throughout the school period according to difficulty. It is assumed that the learner’s role was to gain proficiency in the mastery of these linguistic elements (McLaren, 2004).

According to Palmer (1957, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001), “There are three processes in learning a language: receiving the knowledge or materials, fixing it in the memory by repletion, and using it in actual practice until it becomes a personal skill” (p. 136).

Situational syllabuses

The culmination of the British tradition established by Sweet and Palmer is the work of Hornby, who is probably best known for his Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English, first published in 1954. He united the tradition of oral method advocated by Palmer and the concern of Sweet and Jespersen with connected text.

He termed his method the Situational Approach, as each new pattern or lexical item should be introduced to the class in advance of the work with the text, and the presentation be linked to classroom situations in which the meaning of the new item would be established. Hornby’s Guide to Patterns and Usage in English, also first published in 1954, is based on a graded and sequenced language syllabus together with procedures for introducing each new item (White, 1988). According to Howatt (1984):

The importance Sweet attached to accurate pronunciation as the foundation of successful language learning made it imperative for the learner to acquire a knowledge of phonetics himself (p. 184).

Sweet drew the threads of his methodology together in a graded curriculum consisting of five stages. First, there was the Mechanical Stage during which the learner concentrated on acquiring a good pronunciation and becoming familiar with phonetic transcription.

The second, Grammatical Stage, was described in detail in the Klinghardt experiment. The learner began to work on the texts, gradually building up his knowledge of the grammar and acquiring a basic vocabulary.

The third, Idiomatic Stage dealt almost exclusively with the learner’s lexical development. This completed the basic course, while Stages Four and Five (Literary and Archaic respectively) were university-level studies devoted to literature and philology.

Malcolm Skilbeck’s Situational Curriculum Model has two particular attractions. Firstly, it begins with situations, hence its name. That is, it’s a way or reaching an understanding of the educational environment as it is at the moment, rather than promoting a Utopian plan for a future dwelling (White, 1989). Secondly, it makes provision for drawing on the ends-means or objective model on the one hand, and the process model on the other.

Trialability is an aid to the successful diffusion of an innovation, and in this respect, Sweet’s proposals were in advance of their time. In comparison, Palmer, though having a most important influence on the evolution of British ELT, was much less successful in installing his innovations within the Japanese educational system, for reasons which are largely to do with the problems of curriculum innovation and management (White, 1989).

Pittman (1963, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001) states that “before our pupils read new structures and new vocabulary, we shall teach orally both the new structures and the new vocabulary” (p. 186).

According to White (1988), in spite of its name, his approach was not situational in the more commonly used sense of contextualizing language in ‘real life’ situations found outside the classroom.

Notional/Functional Syllabuses

There has been a movement away from grammatical syllabuses, and then situational syllabuses, to what are variously described as notional/functional or communicative syllabuses. According to Munby (1978), a major factor has been the work of Trim and his colleagues, especially Wilkins, in the Council of Europe Programme for a unit/credit system for adult language learning.

Another line of development in this movement has been strongly influenced by the work in discourse analysis of Widdowson, Sinclair, Candlin, Trimble and their colleagues.

According to Wilkins (1976, 1979, as cited in Widdowson, 2003), such a syllabus consists of two sets of notional categories. The first are ‘semantico-grammatical categories’ which include the kind o functions which would be accounted for in a Hallidayan functional grammar. The second set is ‘categories of communicative function’ and these are pragmatic in nature, and have to do with functions in the Hymes sense.

According to White (1988):

The 1970s were characterized by a concern with meaning, and this was to form the basis of the Council of Europe’s ‘Threshold Level’ or ‘T-Level’ project, initiated in 197s. whereas the structural approach to language had emphasized differences among languages as revealed in contrastive analysis, the ‘notional-functional’ approach, as it came to be called, emphasized that all languages expressed the same meanings, but with differing structural realizations (p. 17).

The most influential of functional/notional syllabuses were the Threshold Level (Van Ek, 1975) and Waystage (Van Ek & Alexander, 1977, as cited in Hutchinson & Waters, 1987) syllabuses produced by the Council of Europe.

The move towards functionally based syllabuses has been particularly strong in the development of ESP, largely on the pragmatic grounds that the majority of ESP students have already done a structurally organized syllabus, probably at school. Their needs, therefore, are not to learn the basic grammar, but rather to learn how to use the knowledge they already have (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987).

The functional syllabuses, however, had their own drawbacks. They suffered in particular from a lack of any kind of systematic conceptual framework, and as such didn’t help the learners to organize their knowledge of the language (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987).

According to Richards and Rodgers (2001), Wilkins’s original notional syllabus model was soon criticized by British applied linguists as merely replacing one kind of list (e.g. a list of grammar items) with another (a list of notions and functions). It specified products, rather than communicative processes.

According to Widdowson (2003), two points need to be made about functional/notional syllabi. First, it is an expression of belief and not an empirical finding. Second, what empirical evidence we do have from language users rather than language analysts suggests that on the contrary, languages are not perceived as equal and expressions in one are not equivalent to expressions in another.

ESP

Different approaches to language description in ESP have emerged over years. One early approach was based on counting the frequency of linguistic forms in a given register. Barber (1962, 1985, as cited in Basturkmen, 2006) identified the frequency of a number of syntactic forms in written scientific prose by analysis of a corpus of texts from a mixture of scientific disciplines (electronics, biochemistry, and astronomy) and genres. This approach was later critiqued for failing to identify the purposes for which the forms were used. Subsequent analyses aimed to identify both linguistic forms and the purposes for which they were used.

EAP

Whereas it was the language expert who traditionally identified needs (e.g. Munby, 1978), more recent approaches have recommended that a number of parties should have a say, including teachers, education authorities, and other stakeholders, such as parents, sponsors, etc. as well as the learners themselves.

Writing specifically about English for Academic Purposes (EAP) contexts, Swales and Feak (1994) note that although many useful insights into academic genres have been provided by corpus studies, many researchers question whether these findings should be unquestioningly transmitted by teachers – and unquestioningly imitated by students.

There were also hundreds of websites offering downloadable materials to ESOL teachers and learners. Some of these were global courses, some were USA specific and some were UK specific. Most of the materials on offer, however, were grammar or vocabulary drills which were no different in content or methodology from those to be found in the majority of EFL coursebooks.

For example, a downloadable series of Activity Sheets (Community ESOL Materials for Classroom Use by ESOL Teachers] developed by Hillingdon Adult Education consists mainly of grammar and vocabulary sentence completion and matching exercises and makes no reference to or use of the English outside the classroom (Tomlinson, 2008).

Content-based Instruction

Content-based Instruction (CBI) has become a significant part of second and foreign language teaching over the past three decades (Celce-Murcia, 2001; Met, 1999, as cited in Harwood, 2010). The need to teach language in a meaningful context, particularly in English for Academic Purposes (EAP) is buttressed by the work of Cummins (1980, 1981, 1996, as cited in Harwood, 2010), which suggests that it takes ESL students five to seven years to become proficient in English at the level required of university students. This is known as Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP).

As Snow, Cortes and Pron (1998, as cited in Pinar, 2003) explain, there are three categories for the content to be covered. These are procedural, attitudinal, and cross-curricula:

The Procedural content refers to the “how to” of language: skills, processes, strategies, and methods. The Attitudinal content refers to the set of rules, values, virtues, and attitudes, both personal and social, that will underlie all the activities in the English classroom. Cross-Curricular content refers to topics or themes that do not belong to any special discipline but reflect the whole of the National Curriculum (p. 10).

Context + Content

Tomlinson, Edge and Wharton (1998, as cited in Harwood, 2010) stress the need to design coursebooks for flexible use so as to capitalize on ‘teachers’ capacity for creativity’. Maley (1998, as cited in Harwood, 2010) provides practical suggestions for “providing greater flexibility in decisions about content, order, pace and procedures” (p. 280). Jolly and Bolitho (1998, as cited in Harwood, 2010) advocate the following principled framework for contextualized realizations of materials:

- Identification of the need for materials

- Exploration of need

- Contextual realization of materials

- Pedagogical realization of materials

- Production of materials

- Student use of materials

- Evaluation of materials against agreed objective (pp. 97-98)

Task-based Syllabuses

With the shift to communicative language teaching in the 1970s, there was an increasing emphasis on using language to convey a message, and as a result, increasing attention was given to the use of tasks in the classroom (Nation & Macalister, 2010). The realization that many so-called communicative language courses were still largely based on a sequence of language forms in turn generated interest in task-based, rather than task-supported, syllabuses.

Published experimentation with task-based syllabuses largely began with the work of Prabhu (1987, as cited in Nation & Macalister, 2010).

In Bangalore and in the British Council in Madras, another approach was presented, which was referred to as ‘The Bangalore Project’, ‘The Bangalore Madras Project’ or ‘The Procedural Syllabus Project’, but the project team itself used the term ‘Communicational Teaching Project’ (Prabhu, 1987).

This was that the development of competence in a second language requires not systematization of language inputs or maximization of planned practice, but rather the creation of conditions in which learners engage in an effort to cope with communication (Prabhu, 1987). In this regard, he (1983, as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 2001) argues:

The only form of syllabus which is compatible with and can support communicational teaching seems to be a purely procedural one – which lists, in more or less detail, the types of tasks to be attempted in the classroom and suggests an order of complexity for tasks of the same kind (p. 4).

Needs analysis

The need for convincing precision in educational needs assessment was reinforced during by the ‘behavioral objectives’ movement in educational planning, particularly in North America, which insisted on specifying in measurable form all goals of importance within an educational system (Richards, 2001).

Needs analysis was introduced into language teaching through the ESP movement. From the 1960s, the demand for specialized language programs grew and applied linguists increasingly began to employ needs analysis procedures in language teaching. By the 1980s, ‘needs-based philosophy’ emerged in language teaching, particularly in relation to ESP and vocationally oriented program designs (Richards, 2001). In this response, Brindley (1998) argues:

Since there is a direct link between attainment targets, course objectives and learning activities, assessment is closely integrated with instruction: what is taught is directly related to what is assessed and (in theory at least) what is assessed is, in turn, linked to the outcomes that are reported (p. 52).

According to Long (2005),

In some respects, the NA literature is reminiscent of writing on language pedagogy 20 years ago, when authors wrote data-free books and journal articles recounting their alleged success at teaching this or that structure or skill, while offering no evidence that what they described had worked at all or worked better than alternative methods (p. 2).

Humanistic Education in Curriculum

Criticism of early needs analysis work led to a change of emphasis, with a greater focus on the collection and utilization of ‘subjective information’ in syllabus design. This change in emphasis reflected a trend towards a more humanistic approach to education in general. Humanistic education is based on the belief that learners should have a say in what they should be learning and how they should learn it, and reflects the notion that education should be concerned with the development of autonomy in the learner.

Apart from philosophical reasons for weaning learners from dependence on teachers and educational systems, it is felt, particularly in systems where there are insufficient resources to provide a complete education, that learners should be taught independent learning skills so that they may continue their education after the completion of formal instruction (Nunan, 1988).

Reconceptualization

The 1973 curriculum conference followed from a previous tradition. Janet Miller (2005, as cited in Slattery, 2006) contends that Paul Klohr, at a 1967 conference at Ohio State University titled “Curriculum Theory Frontiers,” inspired the Reconceptualization. Among the most significant figures in the curriculum field, Klohr helped to organize this conference to honour the twentieth anniversary of a 1947 conference held at the University of Chicago, titled “Toward Improved Curriculum Theory,” which included participants Hollis Caswell, Virgil Herrick, and Ralph Tyler. Indeed, curriculum theory has been around for a long time, and new ways of thinking were fermenting in many circles prior to the1973 Rochester conference that signaled the Reconceptualisation of curriculum studies was under way.

According to Pinar (2003), “Until the reconceptualization of U.S. curriculum studies during the 1970s, there was too complete an institutionalization of the field, with insufficient distance from the schools, state departments of education, and politicians’ rhetoric” (p. 7).

Conclusion

The most recent realization of a competency perspective in the United States is seen in the ‘standards movement’, which has dominated educational discussions since the 1990s (Richards, 2001). Standards are descriptions of the targets students should be able to reach in different domains of curriculum content, and throughout the 1990s, there was a drive to specify standards for subject matter across the curriculum. These standards or benchmarks are stated in the form of competencies.

References

- Basturkmen, H. (2006). Ideas and opinions in English for specific purposes. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Brindley, G. (1998). Outcomes-based assessment and reporting in language learning programmes: A review of the issues. Language Testing, 15(1), 45-85. doi:10.1177/026553229801500103

- Brown, J. D. (1995). The elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

- Cook, V. J., & Newson, M. (2007). Chomsky’s universal grammar: An introduction (3rd Ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

- Feak, C. B., & Swales, J. M. (1994). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills. Michigan: Michigan University Press.

- Harwood, N. (2010). English language teaching materials: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Howard, J. (2007). Curriculum development. North Carolina: Elon University.

- Howatt, A. P. R. (1984). A history of English language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for specific purposes: A learner-centered approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Long, M. H. (2005). Second language needs analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Munby, J. (1978). Communicative syllabus design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nation, I. S. P., & Macalister, J. (2010). Language curriculum design. Madison Ave, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nunan, D. (1988). Syllabus design. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pienemann, M. (1998). Language processing capacity. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.). Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 679-715). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Pinar, W.F. (2003). International handbook of curriculum research. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Richards, J. C. (2009). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2nd Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Slattery, P. (2006). Curriculum development in the postmodern era (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Tomlinson, B. (2008). English language learning materials: A critical guide. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- White, R. V. (1988). The ELT curriculum: Design, innovation and management. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, Ltd.

- White, R. V. (1989). Curriculum studies and ELT. System, 17(1), 83-93. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(89)90063-8

- Widdowson, H. G. (2003). Defining issues in English language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Willis, D. (1990). The lexical syllabus. Collins: Collins ELT.

- Willis, D. (1990). The lexical syllabus: A new approach to language teaching. London: Collins ELT.

- Willis, D., & Willis, J. (2007). Doing task-based teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

How to cite this article in APA Style?

Hariri Asl, M. H. (2023). The history of language curriculum development. LELB Society, https://lelb.net/history-language-curriculum-development/